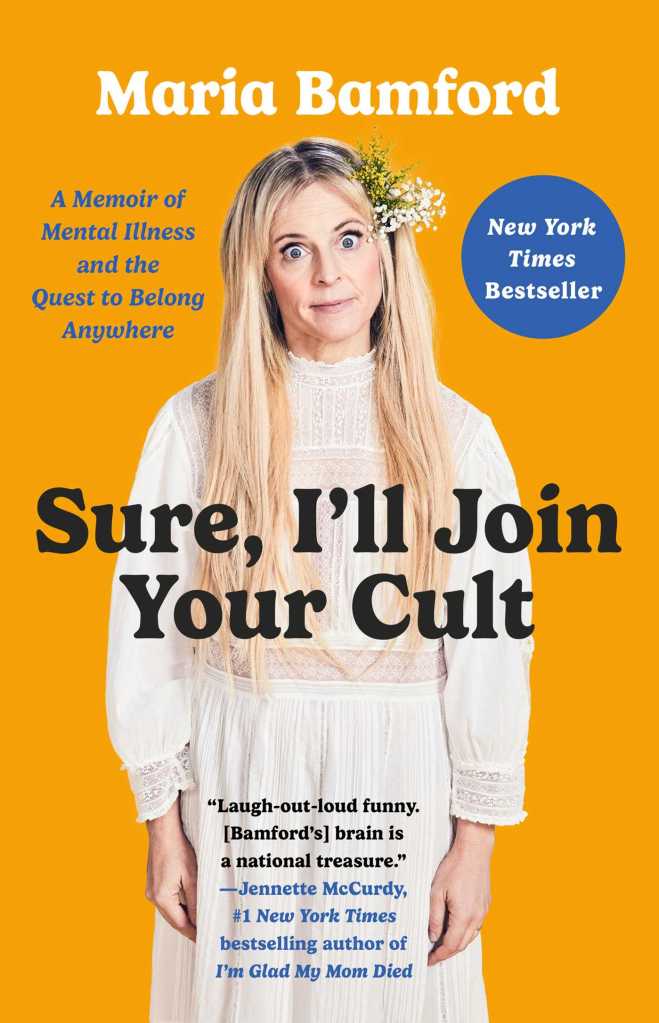

Sure, I’ll Join Your Cult

Have you ever joined a cult? Have you ever watched Midsommar and thought, “okay, but like, if you survive, this place would be pretty dope?” Have you ever wished ConcernedApe would make a new game about building and growing your own compound? You are not alone– and Maria Bamford would likely say there’s a 12-step program for it.

After all, in her book Sure, I’ll Join Your Cult, Bamford explores in great detail her deep-rooted desire to finally find a sense of belonging, humorously while being acutely aware of the ways so-called resources are preying on her vulnerabilities. And ironically, she never once deters anyone from escaping their cult-like means of connection; in fact, Bamford admits to still being an active participant in many. Because whether the intentions are pure or not from an organization, Bamford recognizes ways she has made improvements in her mental health journey by participating fully, and unapologetically.

Something I have loved about Maria Bamford is how she realistically portrays her own mental health struggles with an unfiltered approach that welcomes the world to laugh along with her antics without ever once losing control of her narrative. In her approach of radical self-acceptance, Bamford has guided comedians and audiences through what it means to laugh at your own shortcomings without minimizing the weight of the tragedy. That is an impressive feat and helps aid in destigmatizing mental illness as a point of discussion. Maria models the thesis of a Dr. Brene Brown rather well– you can hold guilt without ever needing to falter into shame.

If you are a middle-aged white suburban mom reading this, I am sure you have heard of Brene Brown, author of many popular books including Braving the Wilderness (2017), and Daring Greatly (2012). Brown is a central force exploring the differences between shame and guilt– two words we generally use interchangeably but could not be more different. Brown says guilt is a natural consequence to actions: if you skip a meal, you are hungry. If you don’t pay your bills, you lose electricity. If you hurt someone’s feelings, you might lose their friendship. Shame, on the other hand, is an intrinsic form of self-sabotage. It says that mistakes make you have less value as a human. Shame and guilt are such familiar topics within my therapy office, I probably explain it more often than depression or anxiety– and almost as often as ADHD.

In a direct quote, “The difference between shame and guilt lies in the way we talk to ourselves. Shame says, I am bad. Guilt says, I did something bad” (Brown, 2012). This topic has been taken and reshaped into countless therapist NPC dialogues across the world. I have my own variation listed above– Jennette McCurdy’s therapist had another.

My favorite summary of shame vs. guilt came from another autobiography: Jeanette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died (2022). She says one of her therapists, while treating her eating disorder, refused to stigmatize relapse. McCurdy was allowed to name when she slipped up, but she was not allowed to use terminology that implied losing or starting over. What she states helped her explore recovery was by getting down to the crux of shame vs. guilt: one is productive, and one is not (McCurdy, 2022).

What Maria Bamford does throughout both her comedy routines as well as within her book is address her mental illness where we see how she is found guilty, but without allowing it to metastasize into shame. Bamford never promises she will be healed or cured from some tragic curse bestowed by a witch on her first birthday– if anything, she writes with a contingency plan of what life could realistically look like if her mental health takes a downturn. But what she does in addition, is pause to laugh with her audience about the absurdity of a brain that chronically misfires. In between her low-points, she stays aware enough of how ridiculous her circumstances are and welcomes us into her deep-dark secrets– if only to show at least one person they are not alone. And perhaps to protect another person from needing to join a full-fledged 12-step-cult. All with humor, of course.

If Bamford’s comedy hinged on making herself the punchline—or suggested that her mental illness made her lesser—she wouldn’t have the impact she does. Her power lies in naming her experiences without apology or self-deprecation. Rather than hiding behind euphemisms or secrecy, she brings her full, complicated self to the stage and the page. In doing so, she resists the shame-laden narratives that so often surround mental health in the United States. Bamford doesn’t owe anyone an explanation for how she navigates the world—and she makes it clear she’s not asking for permission, either.

Which parallels another common incident I see in my office. People who are grappling with a chronic condition– whether it be social anxiety, neurodivergence, etc.– getting frustrated, because no matter how many times they seek permission to exist, they feel ridiculed. They get frustrated, because no matter how many times they speak to a stranger, they are still anxious. They have worked with multiple therapists and can never get rid of that pang of anxiety, no matter the coping skill or self-regulation prescribed. What I recognize is the client sitting with a shame spiral that is measured based on a neurotypical standard.

I ask my client, “Have you ever heard the Einstein quote, ‘everyone is a genius. But if you measure a fish by his ability to climb a tree, he’s going to spend his whole life believing he’s stupid?’”

“Yeah,” the client says.

“Have you ever gotten mad at an amputee for not being able to tie their own hair into a ponytail?”

“No.”

“Why are you measuring your skills based on the abilities of someone without your condition?”

Neurodiversity, personality disorders, and chronic mental illness do not constitute perpetual shame for needing accommodations. When a client with social anxiety continues showing up for peers and loved ones while still experiencing anxiety symptoms, that is a lot—and more than enough.

In addition, we’re not fooling anyone about our mental journey. We’ll think we’ve got on an impenetrable mask, but our loved ones see through it. If you have Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, your friends know you believe you have to flick the lights on and off or else you’ll kill everyone in the room. And those people love you not in spite of the OCD, but including the OCD. It does not define you, but it is part of the terms and agreements on how you will be navigating this world.

If Maria had at any point alluded to her own OCD or bipolar disorder as being the thing she needed to defeat, she would be silencing a whole demographic. She would be thrusting the shame-narrative to new heights. Instead, she chose to define her own narrative and radically accept her silly little brain for the sake of giving permission to other individuals to talk about their internal worlds– even if they don’t entirely fit the cookie-cutter prototype. Because when we are so focused on pursuing the world through the lens of “normal,” we are left in an unproductive pursuit of self– completely alone and ashamed of not fitting a shape we were never meant to live in.

But with individuals like McCurdy, Brown, Bamford, and many more, we are seeing that we only feel truly included when we are unapologetically our most authentic selves– warts and all. “True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are. Fitting in is about assessing a situation and becoming who you need to be to be accepted. Belonging doesn’t require us to change who we are; it requires us to be who we are. The opposite of belonging, from the perspective of research, is fitting in” (Brown, 2017).

I’ll say that once more and louder for the people in the back: The opposite of belonging is NOT isolation or loneliness; it is fitting in.

So for today, I will leave you with this: What if there is no cult? What if it’s all just an act? What if the true cult is the friends we made along the way?

References

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Avery.

Brown, B. (2017). Braving the wilderness: The quest for true belonging and the courage to stand alone. Random House.

McCurdy, J. (2022). I’m glad my mom died. Simon & Schuster.

Leave a comment